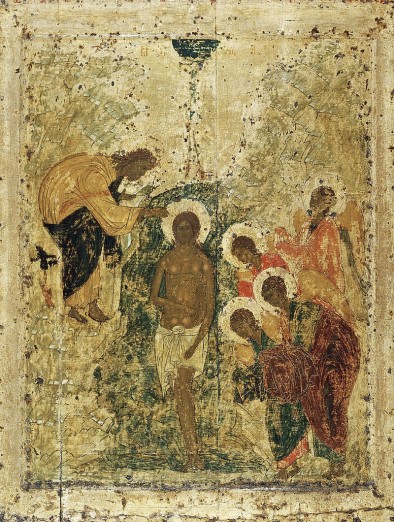

Baptism of Jesus’ ~ Andrei Rublev; Annunciation Cathedral, Moscow

[This essay was translated into Tamil by the magazine Padhaakai and published by them in the January-February issue https://padhaakai.com/2020/02/10/168693/ ]

Russian literature, as we know it, marked its dawn in the eighteenth century under the astral influence of two great men — Derzhavin and Karamazin. Derzhavin was Russia’s first national poet and Karamazin, was the country’s first historian, whose twelve-volume exposition of Russian history is, to this day, a resource of exacting scholarly erudition.

Prior to this, two epic poems dated to the twelfth century remain extant: The Chronicle of Kiev and, The Story of the Raid of Prince Igor. The last, especially, is a much-loved cultural influence and like most such world epics, it too has the strange mystique of being lost and re-discovered. Not once, but twice¹!

Why it took until the eighteenth century for Russian literature to take root and blossom has been a matter of intense scholarly engagement. Despite its geographical continuity with Europe, Russia was unaffected by the changes that swept through intellectual and literary Europe in the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries; changes that came on the heels of the Reformation and the Renaissance. Historians attribute this to the barrier erected by the Great Schism which was to become the forerunner of the Iron Curtain.

But, for a few centuries, a grand cultural and intellectual integration of Europe and Russia did take place; one that has revived in recent times (albeit haltingly), with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Instituted by Peter the Great, these collaborative exchanges were dutifully continued by his successors: The Empresses, Elizabeth and Catherine (Catherine the Great). During this heady period, many of the ideas of the Enlightenment were entertained by the Russian Court² with a monarchy that was attentive to the need for devolution of power and the dismantling of serfdom.

History has many a record of progressive propositions that were abruptly disrupted by the dispositions of circumstance. This time, it was the explosion of the French Revolution that slammed the brakes on what might have been a very different history of Russia. Instead, in the aftermath of the Revolutions, the monarchy sought to stabilize affairs by reverting to its entrenched and familiar practice of autocracy.

Catherine’s grandson, Tsar Alexander I, believed in a limited liberalism and was open to reform but a series of wars, assassination attempts and social unrest caused him to reverse his stance. It was under his grandson, Alexander III — called the ‘Tsar-Liberator’ — that serfs were finally emancipated, serfdom abolished, and the period (in the second half of the nineteenth century) when Russian literature blossomed to its full potential. He secured for literary expression its freedom and allowed it to flourish, unfettered, in his reign.

. . .

‘The Horsewoman’ ~ Karl Bryullov; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

From its radiant start in poetry with Derzhavin and Pushkin, Russian literature blazed an extraordinary trail, unparalleled elsewhere in the world, for the five decades that spanned the period from 1840 to 1890. World literature has no equal to the literary outpouring of this period that birthed the greatest works of Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Larmontov, Afanasy Fet, Blok and a great many others. But for Russian poetry, this was a period of a lull. It stepped back from the limelight and played second fiddle to prose. Happily, it didn’t take long for this interlude to give way to poetry’s glorious second coming in the twentieth century with an avalanche of verse from iconic poets, women and men, who found new ways of expression. Their words have become immortal classics and are translated into many languages around the world.

This extraordinary synchronic response of poetry and literature to the sociopolitical change over two centuries has been mapped into literary epochs based on the primary philosophical sentiment, in each time period, which found literary expression in verse.

- The Golden Age — 1800- 1835): This was the time of Pushkin and his Pleiad. It was an age influenced by the Enlightenment and combined the thought of Neoclassicism and Romanticism³.

- Age of Romanticism — (1835- 1845): The poetLermontov, whose approach to poetry is commonly called Byronic, was one of Russia’s greatest Romantic poets. His influence was great in this time.

- Age of Realism — (1840- 1890): This period marked the rise of the Russian novel. It was the age of Turgenev, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy.

‘Ninth Wave’ ~ Ivan Aivazovsky; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The poet of this age of poetry’s decline was Afanasy Fet. He disavowed the popular belief that art existed for a purpose and espoused, instead, the sentiment that art existed for the sake of art alone. All writers who were not Realists (who did not address social and political causes through their poetry) were condemned by powerful critics⁴ who decried poetry as a medium unfit for the expression of contemporary issues. Consequently, by 1860, there was a camp of ‘civic poets’ who wrote poetry with a purpose; an aim — an aim that was the cultivation of a social conscience. And so, while England, in the sixties and seventies of the nineteenth century, had great poets like Tennyson and Browning and France had Baudelaire and Verlaine; Russia, in her turn, had none⁵.

- The Silver Age and Symbolism — (1890- 1912) A series of reactionary movements and political assassinations caused by anarchists forced both royal and public engagement with progressive reform to thaw. The constant unrest shifted the general mood once again to nostalgia for a seemingly more-peaceful past and ‘art-for-art’s sake’ poetry regained its lost favor. Poets of this age resurrected Fet and Tyutchev and followed the metaphysical motivations of their poetics. The latter half of this period is usually referred to as the period of Symbolism. Ivan Bunin and Alexander Blok were the dominant voices of this time.

Both groups rejected civic verse and reverted to earlier role models for inspiration. Even if French poets Baudelaire and Verlaine remained a potent external influence, this new crop of poets equally relied on homespun experience. This proximal, inward and internal search determined the shape of Russian poetry for the rest of the century. Symbolists diverged from fin de siècle poets by showcasing a distinct theurgic element in their poetics and philosophical outlook. Their belief shifted from the Schellingian⁶ naturophilosophie adopted by Fet to a more directly religious God.

Symbolism was the forerunner of the twentieth century Russian verse that the world grew to venerate and love. It had, at its masthead, the guiding light of two men — one, a poet and the other, a philosopher: Afanasy Fet and Vladimir Soloviev. Their combined influence helped create a new form of verse that had its aesthetics shaped by Fet with the theological overlay of Soloviev.

Despite its reversal to an earlier form of poetry, Symbolism continued to uphold concerns with civic causes and played an integral role in the intellectual ferment of its time. But its structure and form were high-brow — elitist almost — and it soon collapsed into disfavor in the shadow of the Russian Revolution. The centuries old monarchy was dramatically dismantled and overthrown; the Tsar, Nicolas II — the last of the Romanovs — was compelled to abdicate and he, along with his family, was executed. No member of the monarchy survived and the dynasty met its end forever. This cataclysmic series of events set the stage for yet another reactionary literary response.

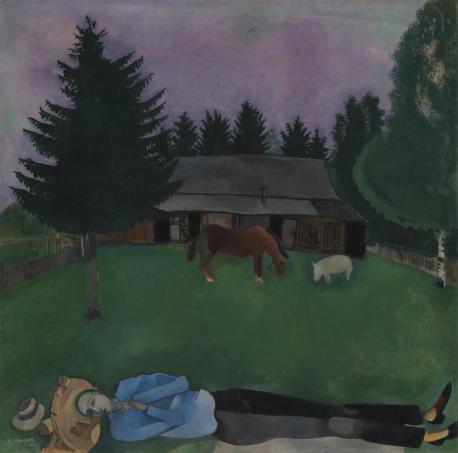

‘The Poet Reclining’ ~ Marc Chagall; Tate Museum, London

- The Era of Modernism — (1912- 1925): Symbolism was now repudiated. Its rejection accreted under two groups who each mounted a separate intellectual response to the tumult of the time. A moderate group called the Acmeists held on to the poetics of Symbolism but distanced themselves from theurgic sentiment. Alongside them formed a more revolutionary group – the Futurists. Together, they are referred to as, Modernists⁷.

The genius that is modernist Russian poetry has four great poets at its pinnacle — somewhat too neatly slotted as two women and two men; two Acmeists and two Futurists. The Acmeists — Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelstam and the Futurists — Maria Tsvetaeva and Boris Pasternak. Two other poets — Mayakovsky and Gumilov were equally significant poets from this period; in fact, Mayakovsky is widely regarded as the poet of the Revolution.

The literary ventures of this group of poets were informed by varied ideological and philosophical approaches. Acmeists rejected the mystical facets of Symbolism alone. The Futurists were more radical. They rejected, in toto, its philosophical underpinnings, language and its ‘disconnect’ from the real world. For them, poetry was a medium that allowed both self-expression and a ventriloquizing voice for societal disaffections. An interesting side-note is that many painters (Cubists) who shared common beliefs on creativity and its purpose banded together with this group of poets and together came to be known as the Cubo-Futurists. Using words and drawing, they sought to express reality as experience — even distort language and formal shape — to provoke opinion and ideation through their art. The painters, Chagall, Kandinsky and Kamensky and the poets, Tsvetaeva and Pasternak, were prominent members of this group.

In the aftermath of the Revolution, the long existing ‘Union of Artists’ was sidelined as a Tsarist Institution. Most of the artists and writers in the Union were strongly opposed to the Revolution and its excesses. Cubo-Futurists were part of the avant-garde group of artists who supported the Bolsheviks and joined the government. They were given control of the Department of Fine Arts and, as the new commissars of art, they adopted the grand task of “constructing and organizing all art schools and the entire art life of the country”⁸. Despite their not insubstantial ideological divide, both Cubo-Futurists and Acmeists credited the inspirational influence of Afanasy Fet for the evolved sound of modern Russian prosody. For his steadfast stance against civic poetry and his insistence that poetry must be written for the sake of art alone — a stand that caused him great isolation and distress — Fet found a posthumous ratification in their veneration.

‘Stalin and Voroshilov at the Kremlin’ ~ Alexander Gerasimov; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

- The Soviet Period— (1925- 1955) The blossom of the Russian novel was like a centennial cactus flower — spectacular but short-lived — and literature began its decline under the authoritarian repressions of the new regime. The end of the civil war in Russia and the entrenching of Bolshevism in the 1920s caused a mass exodus of artists and writers to Europe. Some chose voluntarily to leave while others were actively deported by the government. Expectedly, it had its repercussions on literature and the outcome had contradictory responses within and without Russia’s geographical boundaries.

Poetry, the short story, novellas and drama took its place. Many prose writers took to becoming translators. In 1932, the Communist State decreed that Socialist Realism was to be the sole prescription for poetry. A second and third wave of emigration commenced and built up around the World War and Russian poets and litterateurs now split into ‘Soviet’ and ‘Émigré’ camps. The émigrés were mostly based in Paris and Berlin. With their numbers swelling with each wave of migration they grew to be a sizable number and established two critical reviews one in Paris and the other in Prague⁹.

The divide between the two groups was based on the support of the government. Emigres prided themselves in having stood up to the government; whilst Soviets saw themselves as patriotic and battling authoritarianism from within. The conflict is best capped in the words of one of the prominent Émigré writers, Aldanov: “Emigration is a great sin but enslavement is a much greater one”.

Prominent Émigré writers were Ivan Bunin (Nobel Laureate in 1933), Nabokov, Aldanov and the poetess Marina Tsvetaeva. The Soviets were led by Mayakovsky — the poet of the Revolution¹⁰ and by Sergey Yesenin. Both of them were individualists at heart yet believed in the Revolution in its early years. Yesenin was disillusioned quickly and revolted. His struggle with reconciling his beliefs with those of the revolution led to a dramatic end when he took his own life at the age of thirty. Mayakovsky who was critical of this act of fatalism; followed him a mere five years later.

Émigré literature despite its impoverished beginnings had the opportunity and the rigor to uphold its artistic and intellectual freedom. Soviet literature on the other hand, struggled with upholding the decree of Socialist Realism and was considered to have capitulated. Yet, despite its many faceted shackling, it had a clutch of famous writers in its stable too. Vera Panova, author of ‘Svidanie — The Meeting’ was amongst them, as was the most famous of them all — Mikhail Sholokhov, 1965 Nobel laureate and author of ‘And Quiet Flows the Don’.

- The Post-Stalin era or the Khrushchev Thaw — (1955- )Post-Stalin, the Khrushchev era saw a relative relaxation of control over literary expression in a new politics of de-Stalinization. A new and young generation of poets came to signify this Thaw (a word coined by Akhmatova) Younger poets have tried to bridge the gap between the Soviets and the Emigres who were futurists and Acmeists. The most prominent of them were Yevgeny Yevtushenkov, Voznesensky, Akhmadulina and Joseph Brodsky (1987 Nobel Laureate). Thaw poets took poetry back to the masses by public outreach — returning lyricism to verse, organizing public readings, self-publication and distribution of their work (samizdat) along with audio recordings of readings. Their unusual but successful methods earned them the moniker ‘Estrada poets’ — podium poets.

The poets of this group are loosely grouped as Official poets and Unofficial poets; the former had ties to the official culture and the government; whilst the latter were a more independent minded bunch composed of both Russian and émigré poets. Except for the famous names associated with this period; little is known of the rest of the poets from this period (sometimes referred to as the Bronze Age of Russian poetry). The stigma of affiliation with the Communist regime and the lack of a clear distinction between the two groups are commonly cited as reasons for this gap in knowledge. It was one of their own— Joseph Brodsky — who ensured that their contribution was unforgotten when he acknowledged them in his Nobel speech. Since then and post-perestroika, scholarly interest in this period has renewed.

‘The Bolshevik’ ~ Boris Kustodiev; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

This neat categorization of literary epochs are merely ex post facto lenses through which we attempt to understand the dramatic shifts in literary thought that happened through the East and West halves of Europe. Neither the movements nor the poets slotted under them, subscribed to these strict definitions. In reality, literary movements evolved, regressed into and borrowed a lot from one another. As did their poets. Despite that, the wide-angle view that facilitates such groupings is critical to our understanding of the extraordinary response of literary endeavor through each passing tumult of history, to reconcile the conflicting challenges of art and purpose, of realism and idealism and of objectivity and creativity.

. . .

My love of poetry was given to me by my father. When we were children, he would recite his favorite poems to us and hold us spellbound with his declamation and his patient and measured explanation of word and phrase. This practice continued as we grew older and we often joined in; but his deeply passionate reading rendered in a rich baritone with nuanced modulations of voice was mesmerizing and our voices fell away to listen; rapt and entranced. My earliest recollections of his recitations were poems that he had first learnt from his father — Coleridge’s ‘Ancient Mariner’ and Arnold’s ‘The Forsaken Merman’. It mattered little that it would take us many years to read, assimilate and memorize these poems. These were the poems he first learnt from his own father and were therefore the ones that he imparted as first and beloved tradition. The tradition of declamation succeeded in seeding his own love for words and language in our hearts and, having seeded it, he then assiduously helped us cultivate it; first as teacher, then as a beloved friend and comrade-in-arms. Literature and poetry became a refuge; a retreat into a space which abounded with the eternal companionship of his generous heart and his wide, unfettered mind.

This love for poetry, that he nurtured with foresight, helped keep me aloft through the harrowing experience of relentless loss that was the past decade. This past year, in an especially low moment, I chanced upon an old anthology of Russian poetry¹¹, and fell in love with Russia and its literature again. The book had a potted biography of each author with embedded snippets of their lives; of romance and political intrigue.

These small stories that seemed to hide grand tales were an invitation for a deep dive into the evolution of Russian poetry and literature. It is not common to find, in our collective civilizational stories, a record that so neatly maps political change with literary response, as is found in the Russia of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. The incentive and the impetus for this response, therefore, merits some attention.

From being a primordial method of communication, sound transits through many avatars, from the simple to the complex — from resonance, note, tune and rhythm; from a word, phrase, clause and sentence to the complexity of music and language — and from there, to the many layered facets of meaning. To an understanding that enfolds the higher cognitions of a word — its interpretation, deconstruction, distortion and meta-explication.

Of the literary arts, poetry alone melds the beauty of music to language by weaving rhyme and metre into and with the word strings. Poetry has the ability to describe human sentiment in tight constructions of language and metaphor. A phrase so structured can hold within it the vastness of human experience. This ability gives Poetry the power of alchemy — it causes ordinary and commonplace words to morph, like magic, into a new and profound awareness. Either as recited verse or as song, the seamless union of music and language endears it to the human heart. It is also the reason for its endurance as an art form — the ease of its oral transmission by memorization as poem or as song.

It is unsurprising therefore, that poetry makes the best case for the human spirit through every tumultuous life-change whether experienced personally or through the indirect impact of sociopolitical disruptions in society and nations. In this same fashion and as response to authoritarian excess, poetry became the lodestar of written and verbal expression in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Russia.

While there was a largely synchronous experience of these literary movements across Russia and Europe; their elaboration, mutatis mutandis, is unique to geographical and cultural circumstance. An extraordinary feature of twentieth century Russian verse is its resistance to the free-verse movement that overtook the rest of the world. Here too, the reasons remain political. The harsh intimidations and repressions felt by poets and writers after the revolution were of a degree experienced nowhere else in the world. Any written word that was not in concordance with the diktat of the regime would ensure for its author, an invitation to the Gulag. Many poets took their own lives or simply disappeared into oblivion in the Gulag to be never heard of again. To avoid this fate and as a method of keeping their artistic freedom alive, poets took the ‘subversive’ route of reciting and memorizing verse; not transcribing it. To facilitate the memorization of verse; they held on to traditional rhyme and metre and eschewed the free verse movement. “Hands, matches, ashtrays” was the name given to the ritual of writing in small notes, surreptitiously exchanging them by hand, then memorizing the words and burning the paper to ashes, by the writer Chukosvskaya. It is how this terrible period of history is remembered to this day.

Poets best mirror the vast disconnect between the reality of the ground and the accessible, yet seemingly unattainable, aspirations of people. By articulating the particularities of human experience in universal terms; Russian poetry allowed the word to transcend barriers of culture, geography and language. The genius of its expression is such that, even in translation, it has effortlessly found its place in the acme of world poetry in our time.

. . .

Bibliography and footnotes:

- Recovery stories aid the cultural entrenchment of epics. The first time ‘The Raid of Prince Igor’ was lost and re-discovered was in the seventeenth century by Count Musin-Pushkin. A namesake of the famous author; Count Musin Pushkin was a renowned librarian, epistemologist and botanist. He chanced upon the manuscript in the collection of a fading noble family, procured it from them and oversaw its reprint. Unfortunately, it was burned down, along with all the other contents of the library, in the great fire of Moscow in 1812. Mercifully, another copy was discovered in the papers of Catherine I in 1864 and it is this version that exists today

- Voltaire and Diderot had an especially close relationship with Catherine the Great. Not much came of these exchanges due to the long shadow cast of the French Revolution. The Empress stressed in her letter exchanges with both philosophers, that while she was sympathetic to the need for reform of the serfdom, Russia’s realities entailed their introduction in a slow and contained fashion. Diderot’s visit to Russia and his efforts with the Empress and her Court is the subject of a book ‘Catherine and Diderot’, Robert Zaretsky, Harvard University Press.

- Neoclassicism is the movement in the arts and in philosophy that reverted to classical antiquity for inspiration and as ideal. It was followed by Romanticism which also harked back to the past but to a more recent one. The Romantics were inspired by the medieval ages. Their primary drivers were the mystique of the universe, nature and human emotion; in all of which, they saw a more perfect authenticity and one that was worthy of emulation

- The critic Vissarion Belinsky wielded an extraordinary authority over literary affairs in the Russia of the 1840s. His influence and its impact on Russian literature is chronicled in Pavel Annenkov’s biography, ‘The Extraordinary Decade’; University of Michigan Press Reprint, 2015

- ‘A History of Russian Poetry’ by Evelyn Bristol; Oxford University Press, 1991

- Schelling — one of the trio of philosophers who came to define post-Kantian German Idealism. The other two were Hegel and Fichte

- ‘The Silver Age’ by Sibelan Forrester and Martha Kelly; Academic Studies Press, 2015

- ‘Russian Cubo-futurism 1910–1930, a study in avant-gardism’ by Vahan D. Barooshian; De Gruyter Mouton, 1975

- ‘Contemporary Annals’ was published out of Paris and ‘The Will of Russia’ out of Prague

- “Enough of the petty truths/ Erase the past from your hearts/ The streets are our paint-brushes/ The squares are our palettes” ~ Vladimir Mayakovsky. Ibid 8. p.119. He later said that, in order to sing the Revolution, he had to stamp on the throat of his own song.

- ‘The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry’ edited by Robert Chandler, Boris Dralyuk et al; Penguin, 2015

- Art in this essay is sourced mostly from the Tretyakov Gallery, Wikimedia Commons and Wikiart. I have tried to include art from great artists contemporaneous to each period in an effort to not only showcase their genius but to also cast light on the artistic perception and its visual representation in each epoch

* * *